Green earth pigment is made from a greenish-yellow mineral called celadonite and glauconite, which are types of clay. It has been used in art for thousands of years, with its earliest use being in ancient Egypt.

Green Earth Pigments in Art—Uses, Properties and Colors

Among the numerous types of pigments used throughout history, green earth pigments have been one of the most commonly used materials since ancient times. The pigment has a fascinating history and has been used in art, such as painting, sculpture, and pottery. This article explores the history, properties, and colors of green earth pigments.

Green earth pigments, also known as terre verte or Verona green, is a natural pigment with a grayish-green hue. The pigment is made from a greenish-yellow mineral celadonite, a type of clay. It is considered one of the earliest pigments used by humans and was widely used in ancient times for painting and other artistic purposes. In this article, we’ll look at the properties, colors, and uses of green earth throughout history.

Nature's Diverse Array of Green Minerals

Nature offers a diverse array of green minerals, exhibiting hues ranging from vibrant green to greenish-gray. These powdered minerals possess the remarkable ability to create captivating and colorful surfaces. Their enchanting pigmentation can be attributed to iron(II) silicates, which add to their allure. However, discerning between these green powders proves to be a formidable challenge due to their varying chemical compositions.

The Historical Exploration of Green Earth Pigments

Unraveling the mysteries surrounding these rare minerals was a daunting task for alchemists of the past. The fundamental components of the commonly utilized green minerals consist of iron, chrome, and nickel. In Russia, for instance, a local chromium deposit was exploited for artistic purposes. The chemical composition of this deposit encompasses a hydrated chrome-iron-silicate, resulting in a hue reminiscent of the vibrant viridian green.

The Historical Exploration of Green Earth Pigments

During the Middle Ages in Italy, an abundance of mineral deposits housing green and greenish minerals graced the lands of Tuscany. The astute medieval mineralogist possessed the ability to differentiate between green earth and green copper compounds effortlessly. However, the green earth derived its name from the place of its origin. While specific deposits of certain green minerals were occasionally scarce, the overall regional supply was plentiful. For example, the Livorno region in Italy featured veins and thin layers of epidote measuring up to 1 cm in thickness. The locals would diligently grind these green minerals, utilizing them as pigments. Consequently, there was no significant development of trade surrounding these minerals. The exploration of new light-fast green pigments was always met with enthusiasm.

To accurately interpret Theophilus' literary passage, a comprehensive chemical analysis of Gothic and Roman paintings is imperative. While such an analysis may determine the presence of a particular green mineral substance, it cannot exclude the existence of other substances within the paintings of different artists in diverse cities.

Verona Earth—A Noteworthy Green Earth Pigment

Verona Earth, a noteworthy type of green earth pigment, gained immense popularity near Verona, Italy. Its significance dates back to 1574 when Mercati included it in the catalog of the Vatican mineral collection. Over time, various names such as terra verde di Verona, terra di Verona, Verona earth, and Verona green have been employed to denote pigments originating from this source. Its esteemed reputation influenced the adoption of the name for green earths sourced elsewhere.

Green earth pigments have stood the test of time and have found extensive use in paintings due to their enduring, stable, and non-reactive qualities. These pigments owe their captivating colors to the presence of celadonite and glauconite, minerals with similar chemical compositions but distinct formation environments. Green earths often comprise mixtures of minerals, including chlorite, quartz, feldspar, amphiboles, and clay minerals, such as montmorillonite, illite, kaolinite, and iron oxides. Celadonite is typically found in basaltic volcanic regions, while glauconite, with its grass-green appearance, exclusively forms in marine settings. Visual differentiation between these minerals poses a challenge as they both exhibit a pale, slightly grayish-green shade.

Green earth pigments boast a rich history of global utilization in the art world. Composed primarily of green clay minerals like glauconite and celadonite, these pigments thrive in diverse environments of formation. While glauconite exclusively arises in marine settings, celadonite emerges as an alteration product of basaltic igneous rocks found in specific regions impacted by onshore and offshore volcanic activities.

The composition of green earth pigments is typically a blend of minerals containing celadonite or glauconite alongside other elements like quartz, feldspar, amphiboles, clay minerals such as montmorillonite, illite, kaolinite, saponite, and iron oxides. Distinguishing between celadonite and glauconite proves challenging once these pigments have been ground, as they both assume a pale, slightly grayish-green hue.

Noteworthy deposits of glauconite-bearing green earths have been discovered in Russia, the Baltic States, Bohemia, the southern region of England, and the Missouri River Basin in the USA. Native Americans were known to utilize these deposits, as noted by Gettens (cited in Grissom, 1970). Superior quality green earths were predominantly celadonite-based, renowned for their purity, and required less preparation compared to glauconite-based pigments.

Cyprus boasts significant deposits of celadonite, rendering it a crucial source of the pigment throughout history. Western European Roman art reveals the presence of Cypriot celadonite-based green earths, as identified by Bearat et al. (1996). Verona, too, earned a stellar reputation as a prominent source of this pigment, often regarded as the finest by numerous authors. Another source of celadonite-based pigment is Tirolean (Tyrolian) green earth, derived from the Zillertal region. Brazil also possesses known deposits of celadonite green earth, as documented by Buckley et al. (1978).

Green earth pigments, being stable, non-reactive, and permanent, make them an ideal choice for various painting media. To refine the pigment, impurities are eliminated through processes like washing, grinding, picking, and potentially chemical leaching.

Grissom (1986) has extensively explored green earth pigments, providing valuable insights into their occurrence, characterization, and identification in the realm of art. Vitruvius refers to a green pigment known as creta viridis, while Pliny (77 AD) mentions a pigment called appianum as a type of green earth. The use of green earth pigment transcends geographical boundaries and has been discovered in first-century AD frescoes at Ajanta, India, as well as a Tsimshian stone mask from the Pacific coast of Canada. Rock art from the Southwest United States also reveals traces of green earth pigments (Best et al., 1995).

Cennino Cennini (c. 1400, Clarke MS 590) recommends the use of green earth pigments for various applications in painting. These include underpainting flesh tones, depicting foreground foliage, draperies, and water, and serving as a base for gilding, as an alternative to red bole. Green earth is particularly recommended for watercolor painting and frescoes.

A natural earth color which is called terre-verte is green. This color has several qualities: first, that it is a very fat color. It is good for use in faces, draperies, buildings, in fresco, in secco, on wall, on panel, and—however you wish. Work it up with clear water, like the other colors mentioned above; and the more you work it up, the better it will be. And, if you temper it as I shall show you (for) the bole for gilding, you may gild with this terre-verte in the same way. And know that the ancients never used to gild on panel except with this green.

History of Green Earth

Insights from Historical Texts and Artifacts

Ancient Roman Wall Paintings and Their Use of Terre Verte

Global Presence of Green Earth Pigments in Historical Art

Applications of Green Earth Pigments in Painting

Green earths are a type of pigment used for centuries in paintings due to their permanent, stable, and unreactive qualities. The main coloring agents in green earths are celadonite and glauconite, which have similar chemistries but are formed in distinctly different environments. Green earths may contain minerals, including chlorite, quartz, feldspar, amphiboles, and clay minerals, such as montmorillonite, illite, kaolinite, and iron oxides. Celadonite is typically found in basaltic volcanic areas, while grass-green glauconite forms only in marine settings. Both minerals are challenging to distinguish visually because they appear pale, and slightly grayish-green.

Green earth pigments have been utilized for centuries in art and have a long-standing history of use worldwide. These pigments are composed of green clay minerals such as glauconite and celadonite, which have similar chemical compositions but different formation environments. Glauconite forms authigenically only in marine settings, while celadonite is the alteration product of basaltic igneous rocks found in some areas of onshore and offshore volcanic activity.

Baltic Glauconite, 50X magnification

Green earth pigments are usually a mixture of celadonite or glauconite, along with other minerals such as quartz, feldspar, amphiboles, and clay minerals montmorillonite, illite, kaolinite, saponite, and iron oxides. It isn’t easy to distinguish between celadonite and glauconite when the pigments have been ground, as both appear a pale, slightly grayish-green.

Deposits of glauconite-bearing green earths have been found in Russia, the Baltic States, Bohemia, the south of England, and the Missouri River Basin in the USA. The latter was used by Native Americans, according to Gettens (cited in Grissom, 1970). It would appear that the green earths regarded as having superior quality were celadonite based, which were purer and required less preparation than glauconite-based pigments.

Significant celadonite deposits from Cyprus have been identified as important pigment sources throughout history. Bearat et al. (1996) identified Cypriot, celadonite-based green earths in Western European Roman art. Verona was also a well-reputed source of the pigment and was generally regarded as the best by many authors. Tirolean (Tyrolian) green earth (from the Zillertal) is also a celadonite-based pigment. Other celadonite green earth sources are known from Brazil (Buckley et al., 1978).

Grissom (1986) has extensively reviewed green earth pigments regarding their occurrence, characterization, and identification in art. Vitruvius describes a green pigment he calls creta viridis, and Pliny (77 AD) also mentions the pigment appianum as a green earth. Green earth pigment is used worldwide and has been identified in first-century AD frescos at Ajanta, India, and a Tsimshian stone mask from the Pacific coast of Canada. Green earth has also been recorded in rock art from the Southwest United States (Best et al., 1995).

Cennino Cennini (c. 1400, Clarke MS 590) recommends green earth pigments for underpainting flesh tones, foliage in the foregrounds of paintings, draperies, painting water, and as a base for gilding (as an alternative for (red) bole). He recommends green earth as watercolor paint and for frescoes.

Green earth pigments have been used in art for thousands of years. The pigment was first used in ancient Egypt, where it was used to color pottery and make wall paintings. The Greeks and Romans also used the pigment imported from Asia Minor for frescoes and mosaics. In medieval Europe, green earth was used in illuminated manuscripts and stained glass. During the Renaissance, it became a popular pigment for painting, particularly in the works of Titian and Veronese. In the 19th century, green earth was used by the Impressionists, who used it to capture the essence of nature in their paintings.

Terre verte, found in ancient Roman wall paintings (with prepared pigment discovered in Pompeii ruins), was primarily employed by early Italian artists in tempera, fresco, and oil paintings. However, among the green pigments used in ancient Roman and Pompeiian wall paintings, a substance of richer and deeper hue than terre verte was present. This pigment was produced by finely grinding a type of green jasper, and it has demonstrated excellent permanence.

A Lady Standing at a Virginal

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1672

Oil on canvas

51.7 cm × 45.2 cm (20.4 in × 17.8 in)

National Gallery, London

The Guitar Player

Johannes Vermeer

c. 1670–1672

Oil on canvas

53 cm × 46.3 cm (21 in × 18.2 in)

Kenwood House, London

Use of Green Earth In Vermeer's Paintings

Vermeer's masterful use of color and technique has long captivated art enthusiasts and scholars alike. One of the intriguing aspects of his work lies in the unconventional choice of green earth pigment for depicting certain elements, particularly in the shadows and flesh tones of his paintings.

In Vermeer's early masterpiece, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, the trompe-l'œil curtain showcases a combination of green earth, lead white, and a touch of lead-tin yellow in the lighter tones. This unexpected blend creates a unique visual effect that adds depth and complexity to the composition.

A recent analysis has shed light on another striking application of green earth in Vermeer's oeuvre. In the painting Young Woman Standing at a Virginal, the artist ventured even further by combining green earth with natural ultramarine to paint the dress of the central figure. This bold experimentation with color demonstrates Vermeer's willingness to push artistic boundaries and explore new possibilities.

Johannes Vermeer, A Lady Standing at a Virginal, c. 1670–1672, oil on canvas, 51.7 cm × 45.2 cm (20.4 in × 17.8 in), National Gallery, London

Vermeer utilized green earth pigment to depict the shadowed areas of flesh tones in some of his later works, including Girl with a Red Hat, The Guitar Player, A Lady Standing at a Virginal, and The Allegory of Faith. While the effect of green earth may not be immediately apparent in reproductions, it becomes strikingly evident when viewed firsthand, often leaving viewers slightly unsettled. Rather than aiming for strict naturalism, Vermeer employed green earth for its decorative quality, lending his paintings a distinctive aesthetic allure.

Johannes Vermeer, The Guitar Player, c. 1670–1672, oil on canvas, 53 cm × 46.3 cm (21 in × 18.2 in), Kenwood House, London

Among Vermeer's masterpieces, The Guitar Player exemplifies the captivating effect of green earth. The pigment is prominently used in the depiction of the neck, adding a subtle richness and tonal complexity that enhance the overall composition.

It is worth noting that, historically, green earth had been employed in a similar manner by certain mannerist schools in Europe. However, by the fifteenth century, artists began favoring umbers and other brownish earth pigments for both deeper and lighter shadows in flesh tones. These tones, with their warmer hues, created a more naturalistic effect compared to green earth. Nevertheless, in the Netherlands, some artists from the Utrecht school, with which the young Vermeer may have had some association during his apprenticeship, continued to incorporate green earth into their flesh tones. It is conceivable that Vermeer acquired this technique during his formative years, thus influencing his artistic choices in later paintings.

The question of why Vermeer persistently used green earth in his later works remains a subject of speculation and debate among scholars. The true motivation behind his continued exploration of this unconventional pigment remains elusive, further contributing to the enigma that surrounds Vermeer's art.

Vermeer's distinctive utilization of green earth pigment adds a layer of intrigue and fascination to his already mesmerizing paintings. This unconventional choice exemplifies the artist's willingness to experiment, challenge traditional norms, and create works that continue to captivate audiences centuries later.

Composition and Formation of Green Earth Pigments

Green earth pigments are derived from natural iron, magnesium, aluminum, and silica minerals. The pigment has a grayish-green hue, and its color can range from light to dark, depending on the mineral composition of the clay from which it is made. The pigment is translucent and has moderate tinting strength, making it ideal for creating subtle shades and tones. Green earth pigments are stable, unreactive, and permanent, making them ideal for use in all painting media. They are prepared by washing, grinding, and picking to remove impurities. Chemical leaching of impurities and levigation may also be used to refine the pigment. Green earth pigment is also known for its excellent lightfastness, meaning it does not fade or change color over time when exposed to light.

Two somewhat indefinite minerals, glauconite, and celadonite, are believed to be closely related and serve as the raw materials for the artist's pigment, commonly known as terre verte. Celadonite, the rarer variety, is softer than glauconite, and both minerals likely consist of mixtures. A high-quality green earth can be found near Verona, specifically at Bentonico, north of Monte Baldo. It occurs within cavities of an amygdaloid rock and exhibits a deep olive green color in superior samples, while inferior specimens showcase a celandine or apple green hue. Green earth is sourced from various European and American locations, exhibiting variations in chemical composition. Previous analyses assumed it primarily consisted of ferrous silicate due to its greenish hue. However, more detailed studies have revealed that green earth contains only a small portion of its iron as ferric oxide and is primarily a ferric silicate. An analysis of a fine hue specimen from Monte Baldo yielded the following results:

Green earth shares similarities with hornblendes, differing mainly in the partial substitution of soda for potash and the presence of water. As an alteration product, it is unlikely to undergo further changes, particularly considering that most of the iron within it is fully oxidized.

It's noteworthy that hornblende, although not recognized as a mineral in its own right, is a series of complex inosilicate minerals commonly found in igneous and metamorphic rocks.

Sources of Green Earth Pigments

Stability and Preparation of Green Earth Pigments

To prepare terre verte, the richest and most uniform specimens of the mineral are carefully selected, ground into a fine powder, and washed with rainwater. The resulting pulverized material is then dried. In some cases, the selected fragments are heated and then treated with very dilute hydrochloric acid to remove impurities such as ochre. The remaining undissolved portion is further ground, thoroughly washed, and dried. Most samples of terre verte exhibit perfect stability in both watercolor and oil painting. As an oil pigment, it is semi-opaque or translucent, lacking a significant body. It does not react with other pigments, nor is it affected by them. When used as a ground color or in underpainting with oil or tempera, terre verte may become more prominent over time due to the deepening of its hue and increased transparency of subsequently applied pigments. Certain samples of terre verte may exhibit slight rustiness upon contact with lime hydrate in true fresco painting, likely caused by the further oxidation of some of the ferrous oxide present.

Green earth is sometimes adulterated. A pure sample remains unaffected when soaked with a 25% ammonia hydroxide solution, neither turning bluish (indicating the presence of copper compounds) nor brownish (indicating the presence of Prussian blue).

Green Earth Colors

Green earth pigments have a wide range of colors, depending on the mineral composition of the clay from which it is made. The pigment can range from a yellowish-green to deep green, with variations in between. The color of the pigment can also be influenced by the specific binder used, the amount of pigment used, and the surface on which it is applied.

Uses of Green Earth Pigments

Green earth has been used for various purposes throughout history, from painting to pottery. The pigment is particularly suited for creating subtle and nuanced colors, making it an ideal choice for landscape painting and naturalistic works of art. It has also been used in portraits and figure painting, particularly in the Renaissance period, where it was used to create skin tones and shadows. Green Earth pigment has also been used for decorative purposes, such as in manuscripts and stained glass decoration.

Painting Techniques Using Green Earth

Green earth pigments can be used in various techniques, including watercolor, oil painting, and fresco. The pigment in watercolor is often used as a glaze over other colors to create subtle and nuanced colors. In oil painting, it can be used as a base color, mainly when painting landscapes and naturalistic scenes. In fresco, it is used to create subtle shades and tones in the paintings.

Conclusion

Green earth pigments have been a significant material in art history for thousands of years, with a fascinating history, unique properties, and a wide range of colors. It has been used in various artistic forms, from painting to pottery, and has played a crucial role in creating subtle and nuanced colors in naturalistic works of art. Its excellent lightfastness makes it a durable pigment that has stood the test of time, retaining its vibrancy and color over centuries. Artists continue using Green Earth pigment today, which remains an essential material in art.

References

- Green earth Colourlex. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- Green earth. Pigments through the Ages. www.webexhibits.com. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- Grissom, Carol A.. A Study of Green Earth. United States: Wellesley College, 1974.

- St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. pp. 224–226. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- Common Medieval Pigments. d-scholarship.pitt.edu. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- Varichon, Anne (2000). Couleurs—pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples. Seuil. pp. 210–211. ISBN 978-2-02084697-4.

- Terre Verte. https://www.library.cornell.edu/preservation/paper/4PigAtlasWestern1.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2016.

- Susana E. Jorge-Villar; Howell G.M. Edwards (2021). “Green and blue pigments in Roman wall paintings: A challenge for Raman spectroscopy.” Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 52 (12): 2190–2203. Bibcode:2021JRSp...52.2190J. doi:10.1002/jrs.6118. S2CID 234838065. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- H.G.M. Edwards (2015). Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry. doi:10.1002/9780470027318.a9527. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- G.S.Brady, Materials Handbook, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1971 Comment: p. 610

- R.D. Harley, Artists’ Pigments c. 1600–1835, Butterworth Scientific, London, 1982

- R. J. Gettens, G.L. Stout, Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopaedia, Dover Publications, New York, 1966 Comment: density= 2.5-2.7 and ref. index = 1.62

- Ralph Mayer, A Dictionary of Art Terms and Techniques, Harper and Row Publishers, New York, 1969 (also 1945 printing)

- The Dictionary of Art, Grove’s Dictionaries Inc., New York, 1996 Comment: “Pigment”

- M. Doerner, The Materials of the Artist, Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1934

- R.D. Harley, Artists’ Pigments c. 1600–1835, Butterworth Scientific, London, 1982

- Matt Roberts, Don Etherington, Bookbinding and the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1982

- Thomas B. Brill, Light Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities, Plenum Press, New York City, 1980 Comment: Refractive index = 2.5–2.7 (seems like an error)

- Art and Architecture Thesaurus Online, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabulary/aat/, J. Paul Getty Trust, Los Angeles, 2000

- Pigments Through the Ages: http://webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/greenearth.html: alpha=1.59-1.612, beta=1.609-1.643, gamma=1.61-1.644 (Link to UV Vis spectra)

- C.A. Grissom, ‘Green Earth,’ ‘Artists’ Pigments,’ Vol. 1,1986, cited in note 195, pp. 141–67, esp. pp. 141–3, 148–9. The other, more common, variety of green earth is glauconite, also a clay mineral but of sedimentary origin; celadonite is of volcanic origin.

- Church, A.H. Chemistry of Paints and Painting. London: Seeley and Co. Ltd. 1890. pp. 168–170.

- Béarat et al. (1996) Béarat, H; Pradell; T. Brugger, J. ’Characterization and provenance of celadonites and glauconites used as green pigments in Roman wall painting,’ Abstract of Papers and Posters presented at the International Symposium on Archaeometry, May 20–24, 1996 Urbana, Illinois (1996).

- Best et al. (1995) Beast, S.P; Clark, R.J.H.; Daniels, M.A.M.; Porter, C.A.; Withnall, R. ’Identification by Raman microscopy and visible reflectance spectroscopy of pigments on an Icelandic manuscript,’ Studies in Conservation 40 (1995) 31–40.

- Buckley et al. (1978) Buckley, H.A.; Bevan, J.C.; Brown, K.M.; Johnson, L.R.; Former, V.C. ’Glauconite and celadonite: two separate mineral species,’ Mineralogical Magazine 42 (1978) 373–382.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the origin of green earth pigment?

What is the color range of green earth pigment?

The color range of Green earth pigment can vary depending on the specific mineral composition of the clay from which it is made. It can range from a yellowish-green to deep green, with variations in between.

What techniques can be used with green earth pigments?

Green earth pigments can be used in various techniques, including watercolor, oil painting, and fresco. It can be used as a glaze in watercolor, a base color in oil painting, and to create subtle shades and tones in fresco.

What makes green earth pigment an ideal choice for naturalistic works of art?

Green earth pigment's unique properties, including its moderate tinting strength and excellent lightfastness, make it an ideal choice for creating subtle and nuanced colors in naturalistic works of art.

Why is green earth pigment still used by artists today?

Green earth remains an essential pigment in the world of art due to its unique properties, history, and range of colors. Artists continue to use it today to create subtle and nuanced colors in their works of art.

Color Notes: Green Earth Part 1

Green Earth Pigments

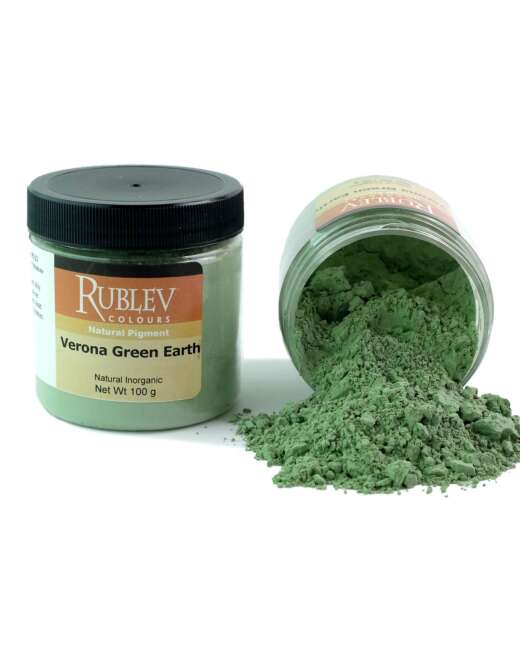

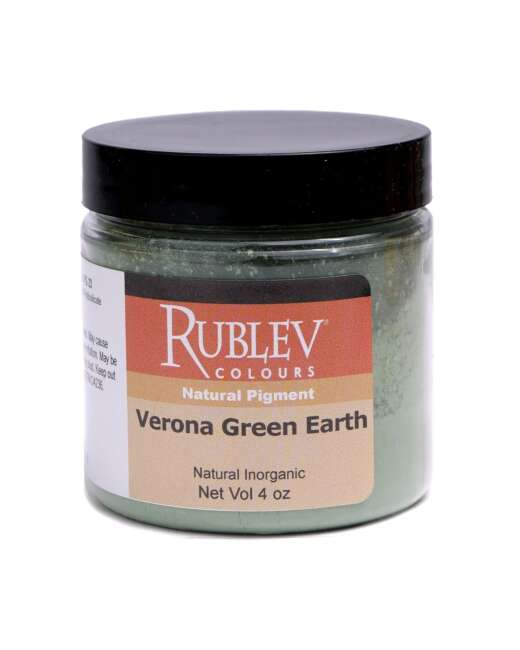

Verona Green Earth

| Pigment Names | |||||||

| Common Names (mineral): | Simplified Chinese: 绿鳞石 Dutch: celadoniet English: celadonite French: celadonite German: Celadonit, Celedonit, Grünerde, Seladonit, Veronit Italian: celadonite Russian: Селадонит Spanish: celadonita, Veronita | ||||||

| Common Names (pigment): | English: green earth French: terre verte German: Grünerde Italian: terre verde Spanish: terra verde | ||||||

| Synonyms (mineral): | Baldogée, Celedonite, kmaite, Seladonite, Verona Earth, Veronite, Yanit | ||||||

| Nomenclature: |

| ||||||

Rublev Colours Verona Green Earth Pigment

| Pigment Information | |

| Color: | Green |

| Pigment Classification: | Natural Inorganic |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Green 23 (77009) |

| Mineral: | Celadonite |

| Chemical Name: | Phyllosilicate mineral |

| Chemical Formula: | K(Mg,Fe2+)(Fe3+,Al)(Si4O10)(OH)2 |

| CAS No.: | Not Listed |

| Series No.: | 2 |

| ASTM Lightfastness | |

| Acrylic: | I |

| Oil: | I |

| Watercolor: | I |

| Physical Properties | |

| Particle Size (mean): | 12 microns |

| Density: | 2.9–3.05 g/cm3 |

| Hardness: | 2.4–2.9 |

| Refractive Index: | nα=1.606–1.625; nβ=1.630–1.662; nγ=1.579–1.661 |

| Oil Absorption: | 40 grams oil / 100 grams pigment |

| Health and Safety | No acute or known chronic health hazards are associated with this product's anticipated use (most chemicals are not thoroughly tested for chronic toxicity). Protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic hazards of this and other chemical products by keeping them out of your body. Do this by avoiding ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhaling spraying mists, sanding dust, and vapors from heating. Conforms to ASTM D-4236. |

Nicosia Green Earth

| Pigment Names | |||||||

| Common Names (mineral): | Simplified Chinese: 绿鳞石 Dutch: celadoniet English: glauconite French: glauconite German: Glauconit, Glaukonit Italian: glauconita Russian: Селадонит Spanish: glauconita | ||||||

| Common Names (pigment): | English: green earth French: terre verte German: Grünerde Italian: terre verde Spanish: terra verde | ||||||

| Synonyms (mineral): | Baldogée, Celedonite, kmaite, Seladonite, Verona Earth, Veronite, Yanit | ||||||

| Nomenclature: |

| ||||||

Rublev Colours Nicosia Green Earth Pigment

| Pigment Information | |

| Color: | Green |

| Pigment Classification: | Natural Inorganic |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Green 23 (77009) |

| Mineral: | Glauconite |

| Chemical Name: | Phyllosilicate mineral |

| Chemical Formula: | (K,Na)(Fe3,Al,Mg)2(Si,Al)4O10(OH)2 |

| CAS No.: | Not Listed |

| Series No.: | 3 |

| ASTM Lightfastness | |

| Acrylic: | I |

| Oil: | I |

| Watercolor: | I |

| Physical Properties | |

| Particle Size (mean): | 10 microns |

| Density: | 2.2–2.9 g/cm3 |

| Hardness: | 2.4–2.9 |

| Refractive Index: | nα-1.592–1.610, nβ=1.614–1.641, nγ=1.614–1.641 |

| Oil Absorption: | 42 grams oil / 100 grams pigment |

| Health and Safety | No acute or known chronic health hazards are associated with this product's anticipated use (most chemicals are not thoroughly tested for chronic toxicity). Protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic hazards of this and other chemical products by keeping them out of your body. Do this by avoiding ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhaling spraying mists, sanding dust, and vapors from heating. Conforms to ASTM D-4236. |

For a detailed explanation of the terms in the table above, please visit Composition and Permanence.

Green Earth Oil Paints

Composition and Permanence

| Verona Green Earth | |

| Color: | Green |

| Binder: | Linseed oil |

| Additive(s): | None |

| Pigment Information | |

| Pigment: | Verona Green Earth |

| Pigment Classification: | Natural inorganic |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Green 23 (77009) |

| Chemical Name: | Phyllosilicate mineral |

| Chemical Formula: | K(Mg,Fe)(Fe,Al)Si4O10(OH)2 |

| CAS No. | — |

| Properties | |

| Code: | 206 |

| Series: | 2 |

| Opacity: | Transparent |

| Tinting Strength: | Low |

| Drying Rate: | Medium |

| Lightfastness: | I |

| Permanence: | A |

| Safety Information: | Based on the toxicological review, there are no acute or known chronic health hazards with the anticipated use of this product. Always protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic hazards of this and other chemical products by avoiding ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhaling spraying mists, sanding dust, and concentrated vapors. Contact us for further information or consult the MSDS for more information. |

Composition and Permanence

| Nicosia Green Earth | |

| Color: | Green |

| Binder: | Linseed oil |

| Additive(s): | None |

| Pigment Information | |

| Pigment: | Nicosia Green Earth |

| Pigment Classification: | Natural inorganic |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Green 23 (77009) |

| Chemical Name: | Phyllosilicate mineral |

| Chemical Formula: | K(Mg,Fe)(Fe,Al)Si4O10(OH)2 |

| CAS No. | — |

| Properties | |

| Code: | 205 |

| Series: | 2 |

| Opacity: | Transparent |

| Tinting Strength: | Low |

| Drying Rate: | Medium |

| Lightfastness: | I |

| Permanence: | A |

| Safety Information: | Based on the toxicological review, there are no acute or known chronic health hazards with the anticipated use of this product. Always protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic hazards of this and other chemical products by avoiding ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhaling spraying mists, sanding dust, and concentrated vapors. Contact us for further information or consult the MSDS for more information. |

For a detailed explanation of the terms in the table above, please visit Composition and Permanence.

Color Notes: Green Earth Part 2

Green Earth Pigments

Tavush Green Earth

| Pigment Names | |||||||

| Common Names (mineral): | Simplified Chinese: 绿鳞石 Dutch: celadoniet English: celadonite French: celadonite German: Celadonit, Celedonit, Grünerde, Seladonit, Veronit Italian: celadonite Russian: Селадонит Spanish: celadonita, Veronita | ||||||

| Common Names (pigment): | English: green earth French: terre verte German: Grünerde Italian: terre verde Spanish: terra verde | ||||||

| Synonyms (mineral): | Baldogée, Celedonite, kmaite, Seladonite, Verona Earth, Veronite, Yanit | ||||||

| Nomenclature: |

| ||||||

Rublev Colours Tavush Green Earth Pigment

| Pigment Information | |

| Color: | Green |

| Pigment Classification: | Natural Inorganic |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Green 23 (77009) |

| Mineral: | Celadonite |

| Chemical Name: | Phyllosilicate mineral |

| Chemical Formula: | K(Mg,Fe2+)(Fe3+,Al)(Si4O10)(OH)2 |

| CAS No.: | Not Listed |

| Series No.: | 2 |

| ASTM Lightfastness | |

| Acrylic: | I |

| Oil: | I |

| Watercolor: | I |

| Physical Properties | |

| Particle Size (mean): | 12 microns |

| Density: | 2.3–3.05 g/cm3 |

| Hardness: | 2.4–2.9 |

| Refractive Index: | nα=1.606–1.625; nβ=1.630–1.662; nγ=1.579–1.661 |

| Oil Absorption: | 40 grams oil / 100 grams pigment |

| Health and Safety | No acute or known chronic health hazards are associated with this product's anticipated use (most chemicals are not thoroughly tested for chronic toxicity). Protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic hazards of this and other chemical products by keeping them out of your body. Do this by avoiding ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhaling spraying mists, sanding dust, and vapors from heating. Conforms to ASTM D-4236. |

Tavush Transparent Green Earth

| Pigment Names | |||||||

| Common Names (mineral): | Simplified Chinese: 绿鳞石 Dutch: celadoniet English: celadonite French: celadonite German: Celadonit, Celedonit, Grünerde, Seladonit, Veronit Italian: celadonite Russian: Селадонит Spanish: celadonita, Veronita | ||||||

| Common Names (pigment): | English: green earth French: terre verte German: Grünerde Italian: terre verde Spanish: terra verde | ||||||

| Synonyms (mineral): | Baldogée, Celedonite, kmaite, Seladonite, Verona Earth, Veronite, Yanit | ||||||

| Nomenclature: |

| ||||||

Rublev Colours Tavush Transparent Green Earth Pigment

| Pigment Information | |

| Color: | Green |

| Pigment Classification: | Natural Inorganic |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Green 23 (77009) |

| Mineral: | Celadonite |

| Chemical Name: | Phyllosilicate mineral |

| Chemical Formula: | K(Mg,Fe2+)(Fe3+,Al)(Si4O10)(OH)2 |

| CAS No.: | Not Listed |

| Series No.: | 2 |

| ASTM Lightfastness | |

| Acrylic: | I |

| Oil: | I |

| Watercolor: | I |

| Physical Properties | |

| Particle Size (mean): | 12 microns |

| Density: | 2.3–3.05 g/cm3 |

| Hardness: | 2.4–2.9 |

| Refractive Index: | nα=1.606–1.625; nβ=1.630–1.662; nγ=1.579–1.661 |

| Oil Absorption: | 40 grams oil / 100 grams pigment |

| Health and Safety | No acute or known chronic health hazards are associated with this product's anticipated use (most chemicals are not thoroughly tested for chronic toxicity). Protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic hazards of this and other chemical products by keeping them out of your body. Do this by avoiding ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhaling spraying mists, sanding dust, and vapors from heating. Conforms to ASTM D-4236. |

For a detailed explanation of the terms in the table above, please visit Composition and Permanence.

Green Earth Oil Paints

Composition and Permanence

| Tavush Green Earth | |

| Color: | Green |

| Binder: | Linseed oil |

| Additive(s): | None |

| Pigment Information | |

| Pigment: | Tavush Green Earth |

| Pigment Classification: | Natural inorganic |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Green 23 (77009) |

| Chemical Name: | Hydrated iron potassium aluminosilicate |

| Chemical Formula: | K(Mg,Fe2+)(Fe3+,Al)(Si4O10)(OH)2 |

| CAS No. | 1317-57-3 |

| Properties | |

| Code: | 211 |

| Series: | 3 |

| Opacity: | Semi-Transparent |

| Tinting Strength: | Low |

| Drying Rate: | Medium |

| Lightfastness: | I |

| Permanence: | A |

| Safety Information: | Based on toxicological reviews, there are no acute or known chronic health hazards with the anticipated use of this product. Always protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic hazards of this and other chemical products by avoiding ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhaling spraying mists, sanding dust, and concentrated vapors. Contact us for further information or consult the MSDS for more information. |

Composition and Permanence

| Transparent Tavush Green Earth | |

| Color: | Green |

| Binder: | Linseed oil |

| Additive(s): | None |

| Pigment Information | |

| Pigment: | Transparent Tavush Green Earth |

| Pigment Classification: | Natural inorganic |

| Colour Index: | Pigment Green 23 (77009) |

| Chemical Name: | Hydrated iron potassium aluminosilicate |

| Chemical Formula: | K(Mg,Fe2+)(Fe3+,Al)(Si4O10)(OH)2 |

| CAS No. | 1317-57-3 |

| Properties | |

| Code: | 212 |

| Series: | 3 |

| Opacity: | Transparent |

| Tinting Strength: | Low |

| Drying Rate: | Medium |

| Lightfastness: | I |

| Permanence: | A |

| Safety Information: | Based on the toxicological review, there are no acute or known chronic health hazards with the anticipated use of this product. Always protect yourself against potentially unknown chronic hazards of this and other chemical products by avoiding ingestion, excessive skin contact, and inhaling spraying mists, sanding dust, and concentrated vapors. Contact us for further information or consult the MSDS for more information. |

For a detailed explanation of the terms in the table above, please visit Composition and Permanence.